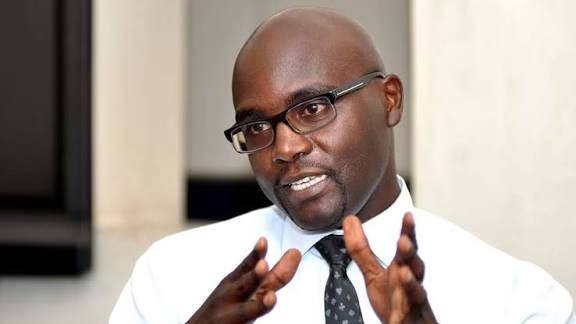

In Kenya today, a single social media post can be the difference between freedom and a prison cell. A few words, an image, or a repost can attract the full force of the state. This is the uncomfortable reality that the arrest of Harrison Nyende Mumia, also known online as Robinson Kipruto Ngetich, has forced the country to confront.

The arrest of Harrison Mumia is not just about one man and one Facebook post. It is about power, fear, free expression, and how far the law can go before it begins to silence the people it is meant to protect.

Who Is Harrison Nyende Mumia?

Harrison Nyende Mumia is a Kenyan activist and the president of the Atheists in Kenya Society. He is not new to controversy. His views are often provocative, challenging religion, politics, and authority. For years, his voice has lived mostly online, where many Kenyans now express what they cannot safely say elsewhere.

In late December 2025, posts appeared on a Facebook account operating under the name Robinson Kipruto Ngetich. The posts included digitally altered images portraying President William Ruto as critically ill and, in some versions, deceased. The images spread quickly. Some people were outraged. Others were disturbed. Many simply shared, commented, and moved on.

For the state, however, the posts crossed a line.

The Arrest: When the State Knocked

On the eve of the New Year, officers from the Directorate of Criminal Investigations arrested Harrison Mumia at his home. His electronic devices were seized. Within days, he was arraigned in court and charged under the Computer Misuse and Cybercrimes Act, accused of knowingly publishing false information likely to cause public alarm.

In legal terms, the charge is framed as protection of public order. In human terms, it is about a man whose words and images placed him on a collision course with the state.

Mumia pleaded not guilty. He was released on bond, but his life is now firmly entangled in the criminal justice system. Court dates, legal fees, public scrutiny, and the psychological weight of prosecution now define his days.

What the Law Says, and What It Allows

Kenya’s Computer Misuse and Cybercrimes Act criminalises the publication of false information, particularly where the publisher knows it to be false and where it may cause panic, discredit a person, or disrupt public order. On paper, the intention appears reasonable. False information can be dangerous. It can inflame tensions and mislead the public.

But the law also carries a dangerous ambiguity.

What is false information in a political environment where satire, exaggeration, symbolism, and protest are part of how citizens speak? Who decides when a post is criticism, when it is art, and when it becomes a crime? And more importantly, is the law applied evenly, or selectively?

These questions sit at the heart of the Harrison Mumia case.

Is the Law Being Used Fairly?

Kenya’s Constitution guarantees freedom of expression. It protects the right to seek, receive, and impart information and ideas. Yet, in practice, this freedom increasingly feels conditional.

In cases involving ordinary citizens criticising or depicting government officials negatively, the response from law enforcement has often been swift and heavy-handed. Arrests are made first. Explanations come later. In some cases, explanations never come at all.

The fear many Kenyans now live with is not just fear of arrest. It is fear of being misunderstood, misinterpreted, or deliberately silenced.

When Criticism Turns Deadly: Remembering Albert Ojwang

Any conversation about arrests over expression in Kenya cannot ignore the painful case of Albert Ojwang.

Albert was arrested after publishing content critical of state actions. He was later reported to have died while in police custody. Authorities initially claimed his death was the result of suicide. His family, human rights defenders, and many Kenyans rejected this explanation, pointing to inconsistencies and unanswered questions.

To this day, Albert’s death remains a scar on Kenya’s conscience.

For many Kenyans, his case represents the darkest fear: that arrest is not just about intimidation, but sometimes about elimination, followed by silence and cover-ups. Whether every allegation is proven or not, the pattern of secrecy, delayed justice, and lack of accountability has eroded public trust.

A Pattern We Can No Longer Ignore

Harrison Mumia’s arrest does not exist in isolation. Over the years, bloggers, activists, students, and ordinary citizens have been arrested for posts, tweets, memes, and videos touching on government officials or public institutions. Some were released quietly. Others were charged. A few disappeared from the public eye altogether.

Each case sends the same message: speak carefully, or do not speak at all.

This pattern matters because democracy does not die in one dramatic moment. It dies slowly, when citizens learn to censor themselves, when fear replaces debate, and when silence feels safer than truth.

What This Means for Harrison Mumia

For Harrison Mumia, the road ahead is uncertain. A criminal case carries consequences beyond jail or fines. It affects reputation, livelihood, mental health, and personal safety. Even if acquitted, the process itself is punishment.

His case will test how Kenyan courts interpret cybercrime laws in politically sensitive contexts. It will also test whether the judiciary can act as a shield for constitutional freedoms, or whether it will allow fear and power to shape legal outcomes.

What This Means for the Rest of Us

If a single Facebook post can lead to arrest, then every Kenyan with a smartphone is potentially one post away from the same fate.

This reality forces difficult questions:

Do we still have space to criticise leadership openly?

Are satire and symbolism protected, or criminalised?

Is the law safeguarding society, or safeguarding power?

These are not abstract questions. They affect journalists, activists, artists, students, and ordinary citizens who use social media as their only public platform.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The answer cannot be silence.

Kenyans must demand clarity in the law, fairness in enforcement, and accountability from law enforcement agencies. Courts must be brave enough to uphold constitutional rights, even when cases are politically uncomfortable. Civil society must continue documenting, questioning, and challenging abuses of power.

Most importantly, Kenyans must remember that rights are not self-enforcing. They survive only when people insist on them.

A Final Word from Legal Express Kenya

The arrest of Harrison Nyende Mumia is a warning. Not just to activists, but to every Kenyan who believes in free expression. It tells us that the digital space is now a legal battleground, and that words have weight in ways we are only beginning to understand.

At Legal Express Kenya, we will continue to tell these stories, not to incite fear, but to promote awareness. Because a society that understands the law is harder to silence. And a people who know their rights are harder to erase.

Leave a Reply